LLMs have a consistency problem. I don’t regard this as an LLM problem or an AI problem but as a systems problem. By this, I mean to say they create a systems problem that can occur at or across any level, and could be resolved at or across multiple levels. The systems problem is that we have trouble integrating inconsistency into our existing systems, and LLMs are a major source of inconsistency.

Let’s say you’re using a personal finance app to manage your money. You want to figure out how much you spend on different categories of expense each month: groceries, rent, utilities, entertainment etc.

The app is connected to your bank account so that every credit and debit transaction gets recorded in your app. Most transactions have really obvious names, and categorizing them can be done automatically. Unfortunately, some transactions have weird names like “S&IU Corp – $58.32”, which turns out to be Hank’s Hardware down the street. Or “CREDIT ACC #242647 – $213.39″ which turns out to be your credit card rewards. Or, of course, “Venmo – $5.00”, which could turn out to be anything.

Luckily, the app developers are working on a machine learning model that can take transaction information and predict which category the transaction belongs to. The model will look at transaction timestamp, amount, merchant name, past transactions, etc. It’s important to you that you get your finances in order, so you’ll review the model predictions and correct anything that the model has mislabeled. Obviously, the less time you spend re-labeling data the better. That is your goal, and it’s the goal of the app developers. After a couple weeks, the app developers have created two models:

- Model A categorizes transactions with 85% accuracy

- Model B categorizes transactions with 50% accuracy

Which model do you pick? Obviously, you would pick Model A. But the aggregate accuracy across all transactions is the wrong thing to focus on. It seems like the correct metric to optimize for, but it’s not. The correct question to ask is this: how consistent is the model in each category?

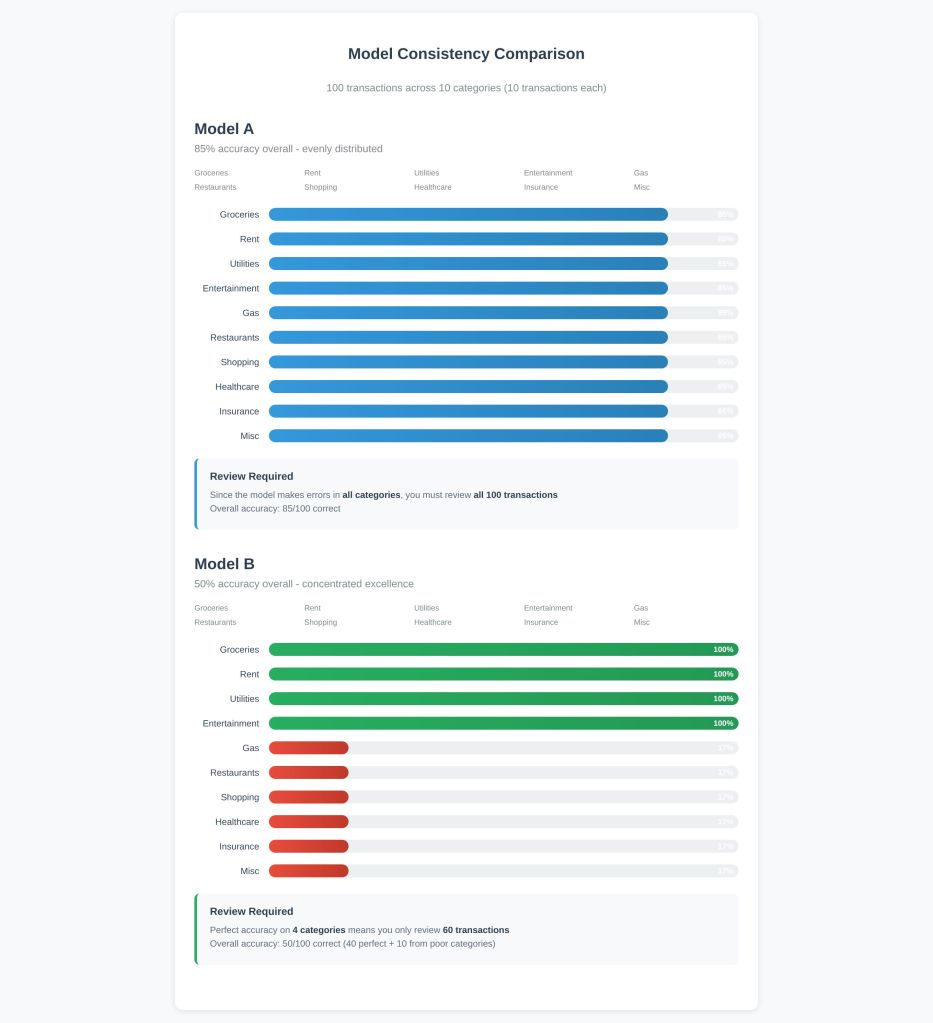

To elaborate, let’s say there are 100 transactions across 10 categories (10 transactions each). Model A is right 85% of the time equally across all categories. Model B is right 50% overall, but it’s 100% accurate on 4 categories and poor on the remaining 6.

Does this framing make a difference to you?

It should. Model A makes errors everywhere, so you have to review all 100 transactions. Model B is perfect on those 4 categories, so you only review 60 transactions. In this scenario, the aggregate performance is irrelevant. What matters is consistency. Our true metric was something like “time that each user spends reviewing transactions,” and the best way to optimize that metric is not to improve aggregate accuracy but to improve the number of categories that are consistently accurate. Understanding and measuring the consistency of a system is far more important than many people realize. I’ve seen the importance of consistency neglected many times both in and outside of ML systems.

A system teaches you how to use it. A consistent system teaches you faster. Is the system consistent? If it’s consistent, then it can be relied upon, and it becomes a potential tool in your workflow. An inconsistent system is hard to use.

We understand this principle intuitively in other domains. One employee might be right 80% of the time, but he’s unpredictably correct — what do you do with that? Another might be right only 15% of the time, but he’s always correct on design decisions. You make that person your chief designer. You can build a great team entirely composed of specialists, each reliable in their domain but terrible outside of it. We understand it with tools too. Google search teaches you how to use it through its consistency patterns. It’s consistently bad at knowing personal information, so you don’t ask personal questions. It’s consistently great at finding nearby restaurants, so you rely on it for that. It’s inconsistent at filtering out promotions, so you’ve learned to stop using it for product research. The tool teaches you its reliable zones.

This same lens is incredibly useful for understanding LLMs. Most complaints about LLMs—hallucination, variance, errors—really boil down to complaints about inconsistency. (For example, a recent MIT study highlights, among other things, the challenges for organizations incorporating an inconsistent but always confident tool into their systems and products.) You can use a tool that’s wrong some percentage of the time, like Google, so long as you know when and where it’s consistently wrong. You can carve out a space in your workflow where you trust this tool. But you can’t use a tool that’s wrong unpredictably. If you don’t know when and where it’s wrong, then you have to review everything it produced, so you might as well have done the task yourself. It’s hard to know how to use this tool to make your life easier.

If the next major LLM release was perfect at just one thing—like fact-checking citations—and absolute garbage at everything else, it would be an incredibly popular tool. If it could perfectly fill the fact-checking-shaped-hole in your workflow you would not care even a little that it doesn’t code, or write limericks, or solve ARC-AGI. Complaints about the things it does poorly would be irrelevant, just like you wouldn’t complain that Google search doesn’t know personal details about your life. LLMs are inconsistent tools, and accordingly they take a long time to teach us how to use them. We’re still on this learning curve. Every new model gets slowly explored across different fronts—coding, creativity, factuality—and it may take weeks for users to converge on reliable use cases: this one for coding, this one for long context, this one for image generation. “Good” here really means “quality + consistency.”

On the other hand, if we keep getting models (or employees, or tools) that are correct 85% of the time, but it’s unpredictable when they will be right, we’re much less certain how to proceed. This isn’t an impossible or unfamiliar problem per se – democracy and majority voting are canonical solutions here, portfolio investment across multiple bets is another solution, in the same way that best-of-n approaches with LLMs try to get the law of large numbers on our side and make good outcomes a numbers game where they cannot be deterministic outcomes. But this is not an elegant solution, nor is it appropriate in some cases where we need guarantees, nor is it really something that meshes with the engineering mindset that drives and adopts LLMs. And of course, in all cases we’re going to find the ceiling, wherever it is, meaning that among a certain population there may be no Einsteins, among a set of companies there may be no multi-billion dollar exit, and among a best-of-n LLM system there will be an upper limit on capability. On the plus side, the best-of-n approach lets you find that ceiling and calibrate when you’ve hit it.

All this to say: consistency matters more than you think.