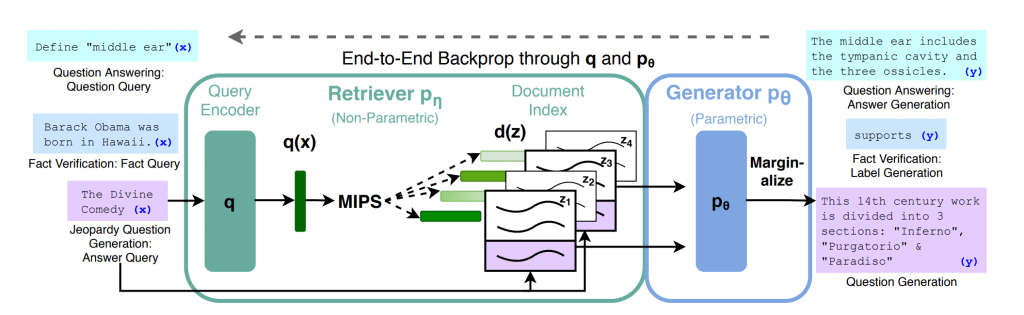

RAG first came out in 2020. (I doubt most people know that “RAG” refers to a specific paper from Facebook.) At the time, I was working on question answering systems, and RAG seemed like the obvious path forward. The best models at the time were seriously hobbled by (among other things) memory and context, and RAG was probably the single most promising research direction to boost chat/Q&A models.

I was so confident in the approach that there’s even a series of webinars where I review, pretty exhaustively, readers, retrievers, and the unified RAG approach, and essentially cover research and toolkit on the entire paradigm.

What happened after that? ChatGPT came along and completely blew previous conversational AI models out of the water. (If I’m talking to someone about this period in time, I’m likely to insist that they interact with BlenderBot 3, which was totally state of the art, came out just a few months before ChatGPT, and is about 50 times worse.)

RAG, which had mostly been a marginal method to help buggy chatbots, became a very useful tool for the new generation of ChatGPT-like models. I would say within a year, and continuing to the present day, the volume of prompt tricks, RAG techniques, and ever-expanding RAG pipeline had exploded.

To be clear, this is fantastic. Instead of having to update my notes every time a RAG paper comes out (almost certainlly impossible today), I can just look up someone else’s survey paper, check out Jerry Liu’s llamaindex write-ups, or scroll through twitter to find out what does and doesn’t work for people. This is vastly preferable to sourcing, reading, and then not having enough time to actually battle test every new idea that comes out.

So, let’s take advantage of someone else’s notes, and do a brief tour through what’s new in RAG. I’ll make this as concise as possible, and list some of the basic / new / more interesting strategies I’ve seen broader consensus on or have tried myself. There are a lot of new, interesting recipes to think about in here, but as always, your mileage will vary for something so very dependent on the dataset, queries, etc.. I won’t cite everything listed, but you should be able to quickly track down what interests you.

Stage 0: Query

- Prompt augmentation/rewriting/expansion

- HYDE: generate a synthetic answer for the search query, then use this as your search query: the synthetic answer is presumed closer to the documents in index.

- Split single query into multiple queries

Stage 1: Indexing/embedding

- Change the model (e.g. MTEB)

- Fine-tune the model: curate data, insert vocabulary, remove vocabulary, etc. every fine-tuning recipe falls under here

- Adding contextual information to document chunks to preserve global context, e.g. prepend the context of the document, like the document summary

- Hierarchical chunking/embedding: document level for first search, sub-document level for second search, etc.

- How to chunk

- Relevant sections, overlapping sections, discrete sections, etc.

- Summarization/synthesis of document before embedding / prepending this

- Metadata for hybrid search or filters: date, keywords, title, filepath, org, entities, etc.

Stage 2: Retrieval

- Reranking – one of the most important “new” components. Find a way to rank your retrieved documents on a metric besides whatever distance metric was used for index search.

- Hybrid search with “sparse” or text-based search. Anything in the TF-IDF family is still incredibly useful (which I’m surprised to see such unanimous agreement on in 2024). I’ve seen even simpler “sparse” schemes provide a lot of value: think number of matching three-grams between query and document.

- The “cross-encoder” scheme seems widespread (iirc this is Cohere’s reranking model, which seems fairly popular). This just means concatenate your query and retrieved document and train a model to predict how good the match between text on the left and right side of the [SEP] token. (Pairwise comparisons into full reranking, or full list-reranking seems less discussed.)

- Custom, holistic re-ranker, of course, where you just stick every piece of evidence you have (rerank scores, keywords, relevance scores, cosine similarity, whatever) and wrap it into an equation, or else stick it into a predictive model (assuming you trust your gold label dataset) to get a final score.

- Summarize, fuse, re-edit, append context to get a tidier (shorter, information-dense) chunk for your ICL, which might otherwise just reiterate context.

Stage 3: Generation

- Post-processing:

- Clean / summarize the answer

- Synthetic reflection and rerunning: is this a relevant, truthful, grounded answer to the question? If not, rerun with feedback about the current answer.

- Multi-hop switches: if the query was about who is the X of Y of Z’s mother, then your first RAG pass might only retrieve knowledge about X and Y, while the second pass can retrieve knowledge about Z, given X and Y and a rephrased query.

I would say the main questions and challenges of the approach are the same: effective embedding and search, relevance of retrieved documents, editing things appropriately before prompting / conditional generation, and of course evals. Agreeing on a gold dataset for something as qualitative as “what’s a good answer to this question” is always more difficult than you think.

What is obviously unchanged is that the use case dominates what you do. What’s the desired wall time on a response? How many vectors do you need to store? Queries per call? How often are you deleting/adding? Do you want a fast/trained index? Which LLM, locally or via API? There are a lot of implementation requirements that can easily make these fancy techniques moot. I find myself coming back to the faiss documentation as a reliable, well-tested, and early vector database project. I’d say the variety of new vector database products in the space today is probably unnecessary, and in many cases you simply don’t need what any of them are offering unless you have a LOT of vectors.

What has changed is better tooling across the board, more steps in the pipeline that probably make a difference instead of just being an over-engineered step. There are more breadcrumbs to diagnose what’s going wrong and where; instead of one monolithic retrieval step that just works or doesn’t, there’s parseable steps you can tackle. Most of all, synthetic editing and generation changes what the pipeline looks like drastically. Of course, infrastructure across the board is better so you can spend more compute / second than you used to, meaning more and more systems are more bottlenecked by quality rather than speed, hence room for more complex and compute-heavy steps in the RAG pipeline.