SUMMARY

********************************

UPDATE

The FAIR authors were kind enough to discuss their work with me and answer some questions.

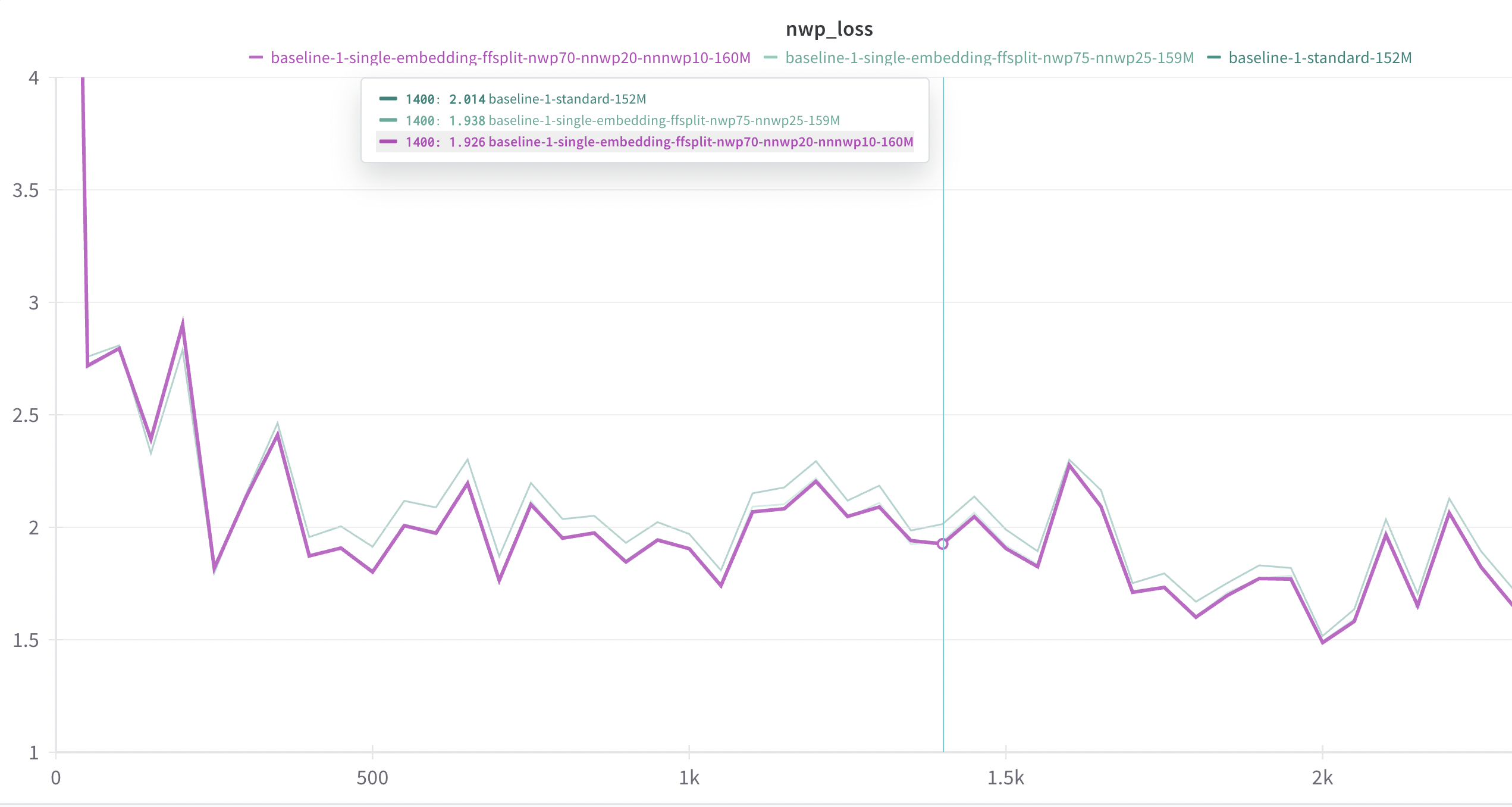

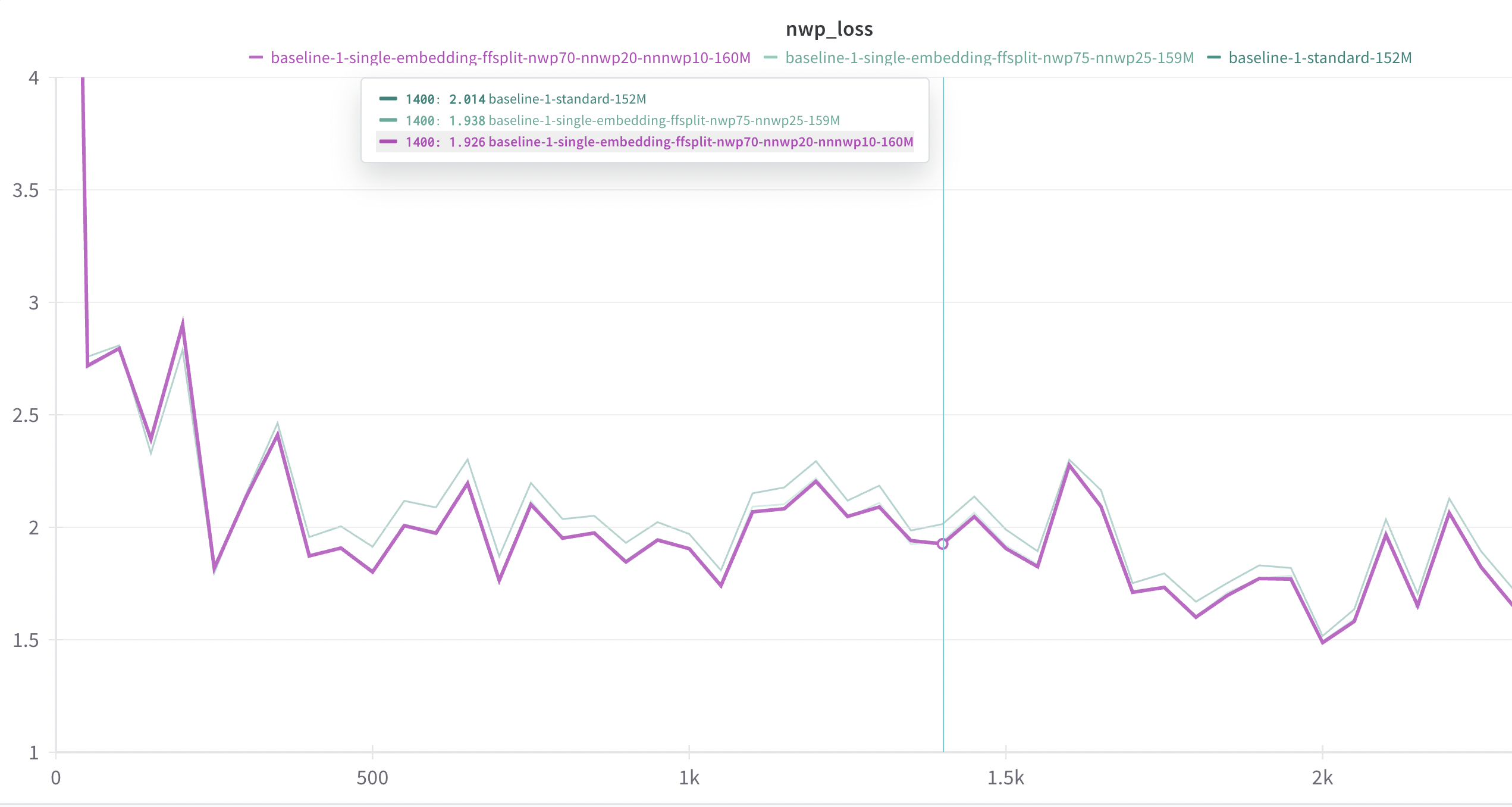

NWP loss: The main point of interest was that on multitoken prediction they saw an isolated next word prediction that was slightly worse (~.1) than a standard model. (Author later publicly tweeted this here so it’s fine to share.) This is interesting in itself because this model was able to perform better on some downstream tasks despite having worse next word prediction performance. The better loss I am seeing with FFSplit remains a mystery that needs to be validated with a longer/larger model experiment.

Architecture: Besides that, the authors did note that FFSplit resembles their linear model mentioned in the appendix, though it says explicitly there are no non-linearities included. The authors note that the architecture didn’t make a large difference so long as the “trunk” is sufficiently powerful. Either way FFSplit uses weighted loss over the token predictions, whereas in the FAIR paper loss is evenly divided over the token predictions, so there are remaining architectural differences.

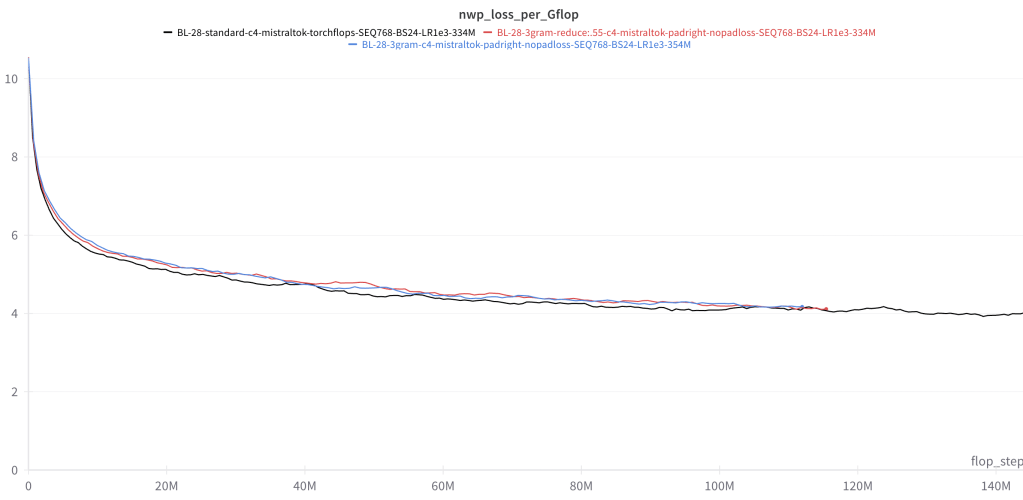

Per-flop comparison: I have also re-run experiments to compare performance per GFLOP to demonstrate how FFSplit’s improved per-iteration performance holds on a per-flop basis. This seems like a simpler and fairer way to evaluate the model against a standard transformer model.

The future of pretraining: I mostly took the paper to be interested in faster inference, but the author did recently tweet that this work “indicate that next-token prediction is not the final form of pretraining losses,” which I have also found to be the more compelling aspect of these experiments.

********************************

Next token prediction is the standard pretraining task for decoder language models. Similar to the FAIR paper published three days ago, we have spent several months exploring next token prediction pretraining coupled with auxiliary tasks. Unexpectedly, this produces models with better loss on the next token prediction task than those that focus entirely on next token prediction. Specifically, models that are pretrained to predict the next additional 2-3 tokens further into the future become better at predicting the next token when compared to standard models that are solely pretrained to predict the next token only.

Crucially, we rule out that the improved loss of these multi-token prediction models is due to other lurking factors like slightly increased parameter counts or increased compute, showing that multi-token pretraining can offer better sample efficiency and language modeling capability. Pending testing at larger scales, this could indicate room for a superior pretraining alternative to next word prediction for general purpose large language models.

The main contributions are:

- Demonstration of lower next word prediction loss for multi-token models

- Experiments to help rule out the possibility that multi-token models are just benefitting from additional parameters / compute.

- A novel architecture (not tested by FAIR authors as far as I can tell), FFSplit, for multi-token prediction that is a good candidate for testing at scale.

Code here, more links below in link section

INTRODUCTION

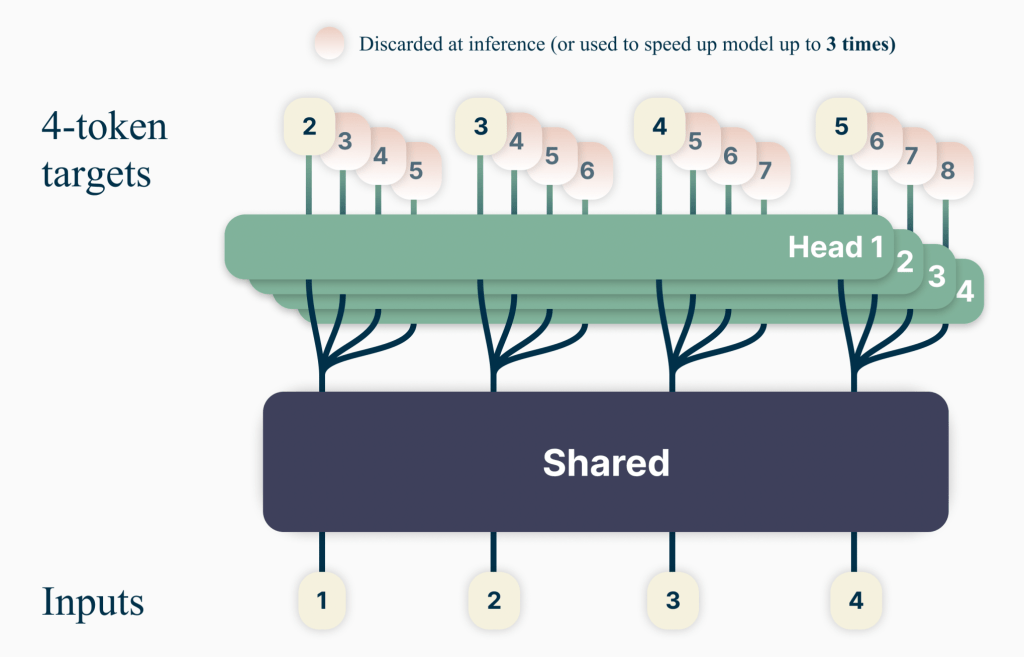

A couple days ago FAIR released a paper called “Better & Faster Large Language Models via Multi-token Prediction”. In this paper the authors train models to predict the next n tokens rather than the next one token only, and show that this pretraining task offers benefits over the standard next token prediction task.

This paper is very similar to a project I have been working on for the last couple months. I am a little disappointed I wasn’t able to wrap up my experiments and share results before the publication of this paper, but am glad to see that the work done so very well (and at scale!) by the FAIR authors is being appreciated by others. It’s a very interesting read so I suggest you take a look.

It is validating to see someone else working on the same problem I have been looking at independently, particularly because the idea (just do multi-token prediction) seemed like it must have been extensively tested already, and there would be minimal room for good results. However, the results of the paper and my own experiments have been incredibly exciting to see.

This post has been quickly put together to detail some of my results on the back of this recently published paper. I will primarily discuss what I regard as my three most important results that I did not see covered in the paper. They are as follows:

- Multi-token pretraining can yield models that are better at next token prediction than models solely dedicated to next token prediction. That is, diverting model capacity away from next token prediction and onto other tasks helps the model at next token prediction better than if there were no auxiliary tasks. This is explicitly demonstrated when we isolate the next token prediction loss of the models and compare them. This is a very persuasive result that I did not see included in the paper.

- Crucially, this result is validated when we run experiments to compare next-token prediction models against multi-token prediction models side by side to isolate the multi-token pretraining task against other confounding factors like discrepancies in parameter count and compute budget. Essentially, under some stress-testing the results still hold.

- The architecture used by the authors (so far as I can tell equivalent to “hydrasplit” in my logs) is one I had tried that did not work especially well. The architecture I have the most success with (called “FFSplit”) was not tried by the authors (again, so far as I can tell – see Appendix B of the paper). Almost all other architectural variations I tried were middling or bad. Additionally, the authors noted that multi-token prediction did not work at small scale, only at large scale. In contrast FFSplit does work at small scale (purely with respect to next word prediction loss – no downstream testing has been performed). Due to personal budget limitations it is unknown if FFSplit works at larger scales, a critical next step for this architecture.

Other than that I will share some similarities / differences / notes between the author’s project and my own, as well as some reasons for you to be excited about possible new pretraining tasks that outperform next token prediction.

MAIN RESULT

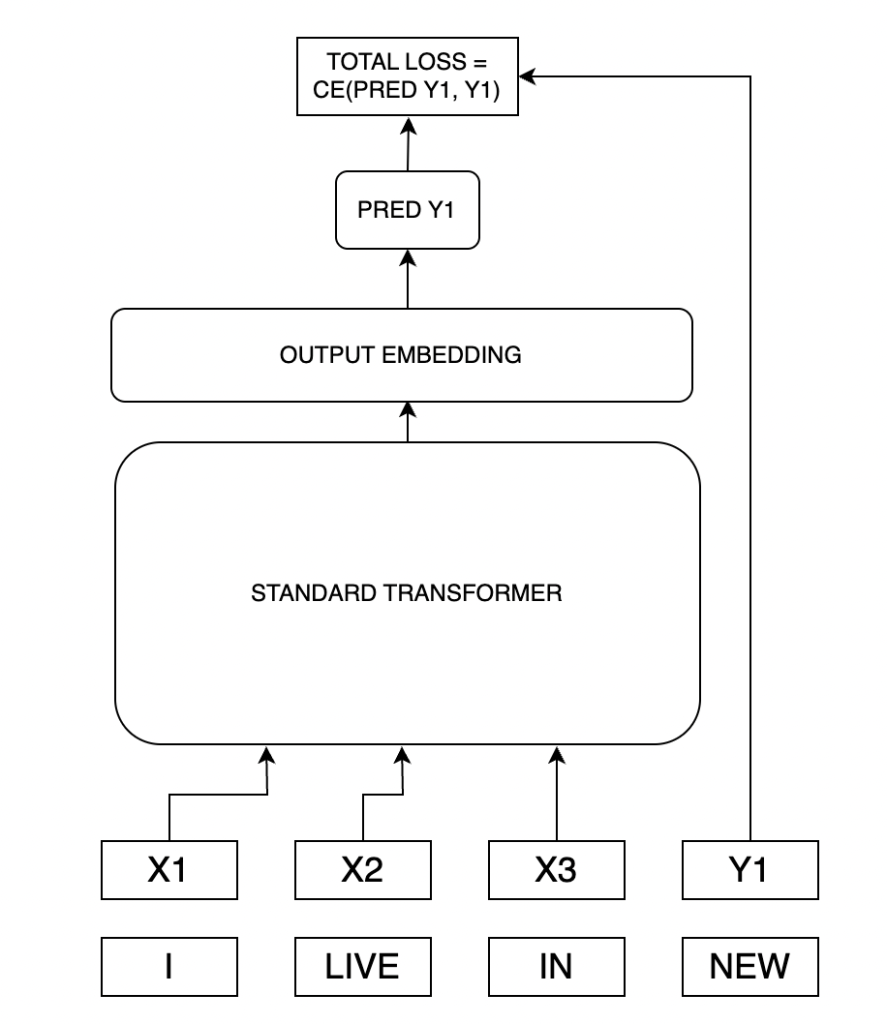

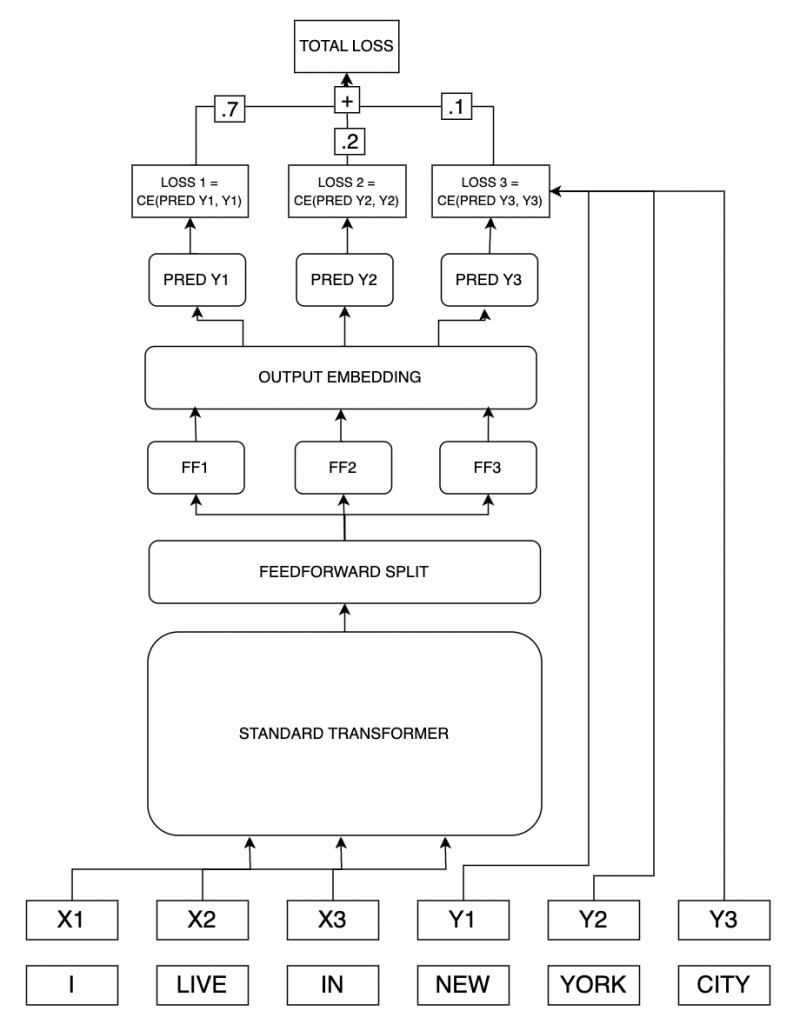

Let’s make a language model that is asked to predict not just the next token, but the next two tokens. We’ll take a vanilla transformer model and modify the architecture just a little bit so that after all the transformer layers, we split the output into two matrices that we’ll feed into the output embedding layer. We’ll predict each token independently, one after another. Let’s make a loss function like so:

Total loss = .75 * (first token loss) + .25 * (second token loss)

How good is this model?

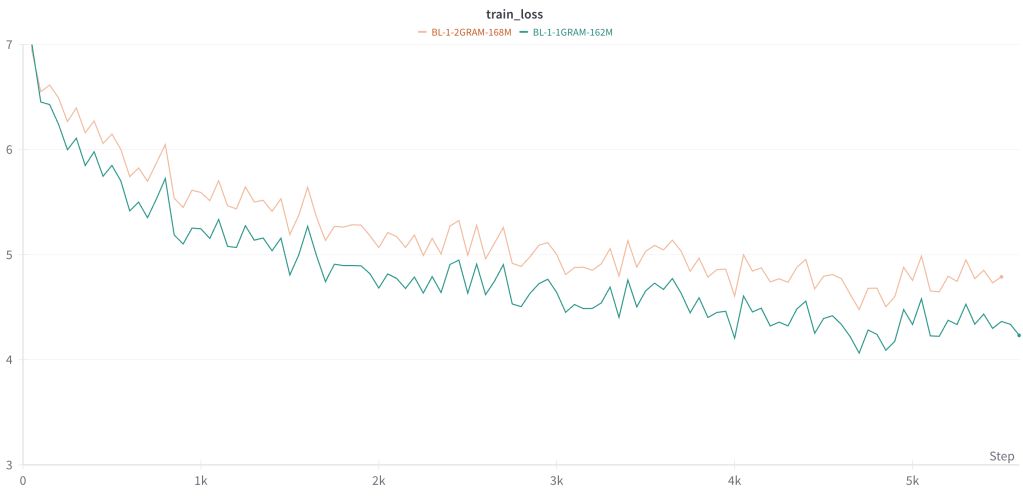

Unsurprisingly, the model that predicts two tokens has much higher loss than the model that only has to predict one token.

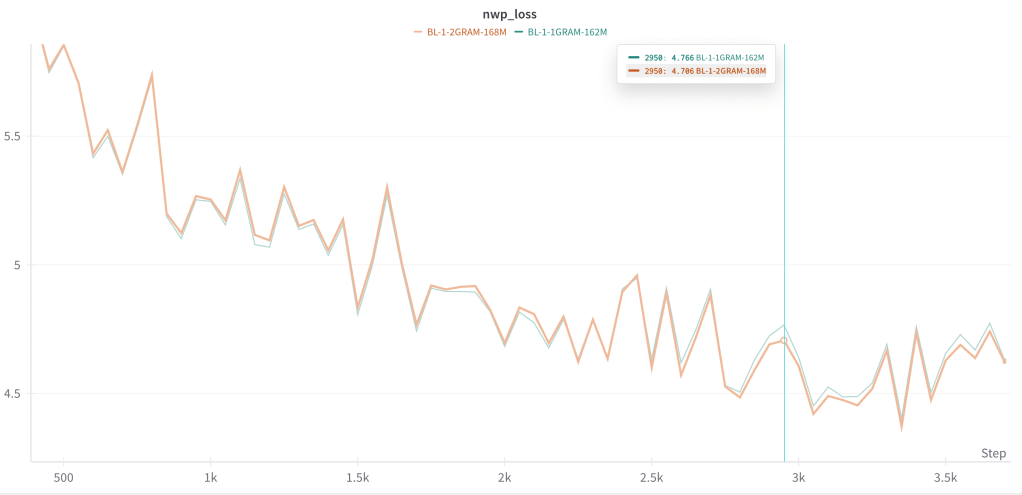

But what if we compare the loss of the next word prediction alone? That is, forget about the total loss and the loss associated with the second token in the 2GRAM model – if we isolate the next word prediction loss, how good is it at predicting the next token vs. the 1GRAM model?

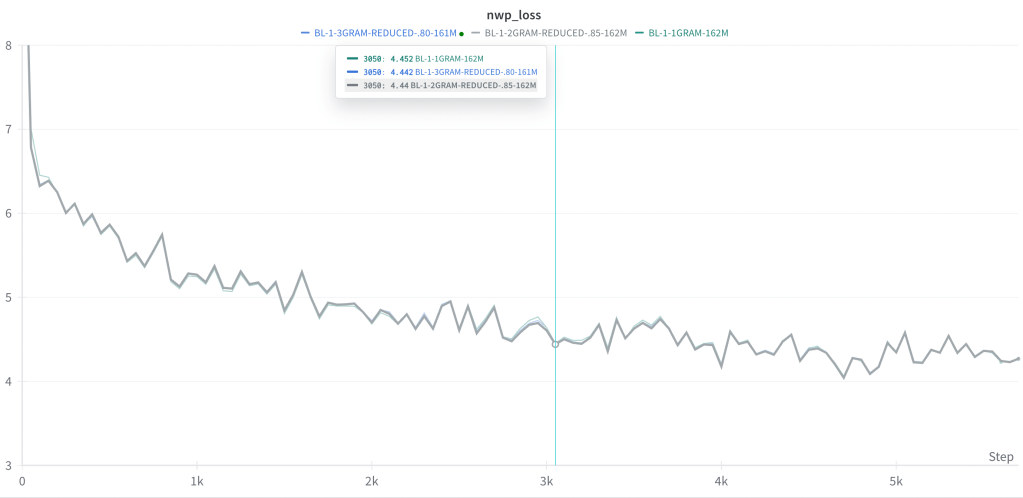

I was very surprised to see the following:

When you isolate the next word prediction loss of a multi-token prediction model it is superior to the loss of a next-token prediction model. That is, a model that is designed to predict the next n words can be better at next word prediction than a model that is solely designed for next word prediction.

This bears out on multiple runs at different (small) scales, for models that predict the next two or three tokens. Typically, the standard (1GRAM) next word prediction model has lower loss on next word prediction, before eventually being slightly overtaken by the multi-token (2GRAM, 3GRAM) models. In no case is the resulting loss differential drastic/huge: there is a modestly lower loss for the multi-token models. However, all else being equal, any improvement over next word prediction as a pretraining objective is incredibly important given the ubiquity and centrality of next word prediction to LLM training.

[I am sorry for the truly horrible naming conventions in these wandb runs. I wanted time to clean them up before presenting but I’ll confuse future work if I rename them. I will caption all pictures appropriately but have added a glossary at the bottom for naming conventions.]

SHOULD WE BELIEVE THESE RESULTS?

I was very skeptical of this result, as you should be:

Point 1: Why would a model that must do tasks A and B be better at task A than a model that focuses solely on task A? Why would the two even have close performance?

Point 2: This is a very obvious and fairly well-studied idea – why would we discover anything useful here that hasn’t been discovered before?

Point 3: There are obvious discrepancies in the models. The 2GRAM model has more parameters. More than that, there is a different compute graph because we are passing through the embedding matrix multiple times.

Point 1 Discussion: At this time I have plenty of speculation but little of substance to add on this question. Nor am I very familiar with multi-task training literature and where else this phenomenon exists. The FAIR paper has some very good discussion in Section 5 and the appendices. (The information theoretic argument is very enjoyable.)

Point 2 Discussion: The “Related Works” section of the paper shares many similar projects I had seen and was not familiar with, not to speak of all kinds of n-gram prediction species of models and tasks before the current LLM era. I was hesitant to pursue this project in any depth because it seems well-trodden, not least of all by ProphetNet, which has maybe had the consequence of discouraging further research in the area (although I wasn’t able to hear back from the authors about research on a decoder-only version).

Pretraining seem underexplored – UL2 and the BigScience paper (both Thomas Wang and Colin Raffel were kind enough to answer a few of my questions on this paper) seemed like the most comprehensive examinations of LM pretraining, but these are mostly focused on scaling over permutations of LM architecture components.

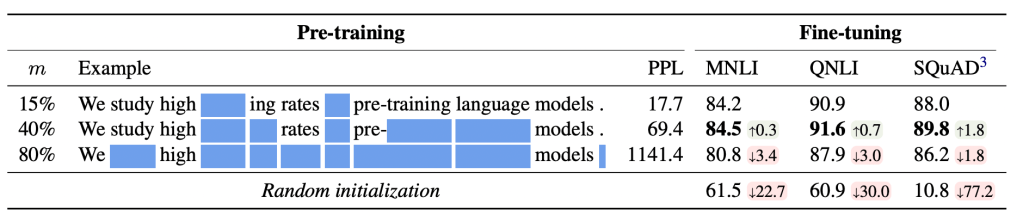

By far the most interesting work here that is completely under the radar (not in the FAIR paper related works) is called “Should You Mask 15% in Masked Language Modeling?” I found the results incredibly surprising: for a BERT-like encoder model, the masking rate has been ~15% since the beginning. (RoBERTa even discarded next sentence prediction and A/B tested the masking rate again iirc.) The authors of this paper found that the optimal masking rate is actually 40%. I’m still not quite sure I believe it, and amusingly enough half of the related works section of our multi-token FAIR paper is a discussion of BERT masking rates that contradict going beyond 15% masking rate:

“…all of these language modeling tasks train on a small percentage of the input text: on average only 15% of the tokens are backwarded through. For Dong et al. (2019), where the masking is done in BERT style, it is hard to mask more than 15% since it destroys too much information. For Tay et al. (2022), it is technically possible to have a larger proportion but in practice, the settings used have between 15% and 25% of masked tokens. (Yang et al., 2019) also makes it possible to train on the whole sequence since it is only permuted, and no information is lost. Yet, in practice, since the completely random permutation is very hard to reconstruct, only 15% are predicted for training stability reasons.”

Anyway, seeing that a BERT-like model can handle such a high masking rate, and that this fact has been so strangely overlooked was good encouragement to start experimenting with more difficult pretraining tasks.

Point 3 Discussion: Following my initial experiments, I was fairly certain that the multi-token models were outperforming the standard model on NWP loss for the following reasons:

CONFOUNDING FACTORS IN OUR RESULTS

Problem 1: Parameter Count

FFSplit introduces extra parameters. While there isn’t a significant parameter increase, it’s unfair to compare models with different parameter counts

Response to Problem 1:

We can create an equal parameter count between a standard and multi-token model by either adding parameters to the standard model or removing parameters from the multi-token model.

While adding parameters to the standard model is straightforward, we should be cautious in doing so: there are many ways to increase the parameter count for a model that will not reliably improve its performance. It is likely, and often happens, that adding an extra layer, or increasing the number of heads, etc. results in a slightly worse model, or one that performs exactly the same. In fact the standard models used for benchmarking in these experiments were carefully selected for their good performance on next token prediction (after testing multiple iterations of different architecture specs). I have designed these models architecture specs to the best of my ability to be “hard to beat,” so scaling them up in a possibly redundant manner didn’t seem like it would necessarily give us a good answer about the strength of multi-token models, though under careful experimentation this can be a valid approach.

Instead we can reduce the parameter count of our FFSplit model by reducing the dimensionality of the output embedding and the associated Feedforward Split layer. Specifically, the model dimensionality is reduced at these last two layers (FFSplit layer and output embedding layer) by some proportion p such that the total parameter count meets parity with the standard model.

This method was chosen in particular for its potential to significantly harm the multi-token models: by reducing dimensionality in the FFSplit layer and output embedding layer, we are removing parameters where they seemingly are most necessary for the task of multi-token prediction. Therefore if the model is still capable even after this reduction, it is a good sign for the model’s resiliency and a testament to the benefit of multi-token training.

In these experiments controlling for parameter count, it is still the case that 2GRAM and 3GRAM models are able to outperform the standard 1GRAM model on next word prediction by a slight margin. It is likely that parameter reduction along less critical components of the architecture, e.g. the transformer layers (called “trunk” in the FAIR paper) would result in even better performance.

Problem 2: Extra Compute

When we predict n tokens, we are making n passes through the output embedding matrix at each iteration (note that it is also possible to simply stack the FFSplit layer outputs along the batch dimension and unstack them after they have passed through the output embedding matrix in parallel, but in practice this is very memory expensive). Therefore the output embedding matrix is receiving more of an update every iteration against the standard model, and besides: we are spending more flops per iteration when compared to the standard model. So the multi-token model isn’t actually better, it just has an output embedding matrix that is training “faster,” so it’s “further along” in training when compared to a standard model on the metric of iterations. A comparison of model performance against flops/training time, rather than training steps, would demonstrate this.

This is particularly troubling for models at small scale. The embedding matrices of a small model represent an enormous percentage of the total parameter count, and a much smaller percentage of total parameter count for large models. This is because the output embedding matrix is of size (vocab_size, model_dimension). As the model increases in scale, the vocab_size stays fixed while the other parameters of the model (dimension, hidden dimension, attention heads, head dimension) all increase. Therefore the larger the model, typically the smaller a percentage of its total parameter count belongs to the embedding matrices. For small models, the percentage can be quite large however.

For example, in some of these experiments, the vocabulary size is >50,000. For a model of dimension 768, this represents a ~40M parameter output embedding against a total model parameter count of 160M. Therefore a slight advantage given to the output embedding matrix would very likely result in a dramatic boost to overall loss. During initial runs my hypothesis was that this is exactly what is going on.

Response to Problem 2:

Scaling

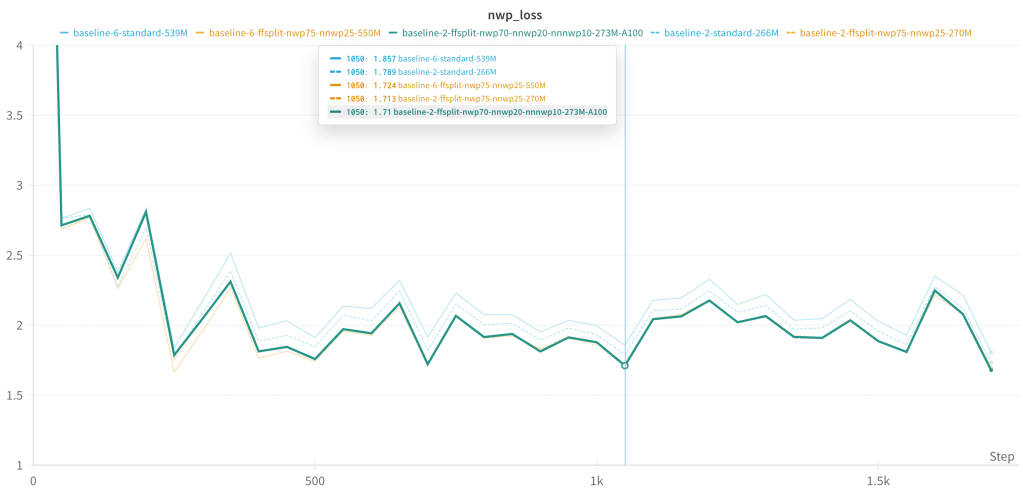

The obvious response is to scale up the experiments. This would result in the output embedding matrix taking up a smaller total percentage of the parameter count. If the results hold while the gap closes on our iteration time / flops per iteration, then the good performance that multi-token models have on next word prediction was likely not simply due to an “faster” output embedding matrix. I was able to scale up to a certain point, and in my few experiments the advantage of multi-token models over standard models on NWP seems to hold:

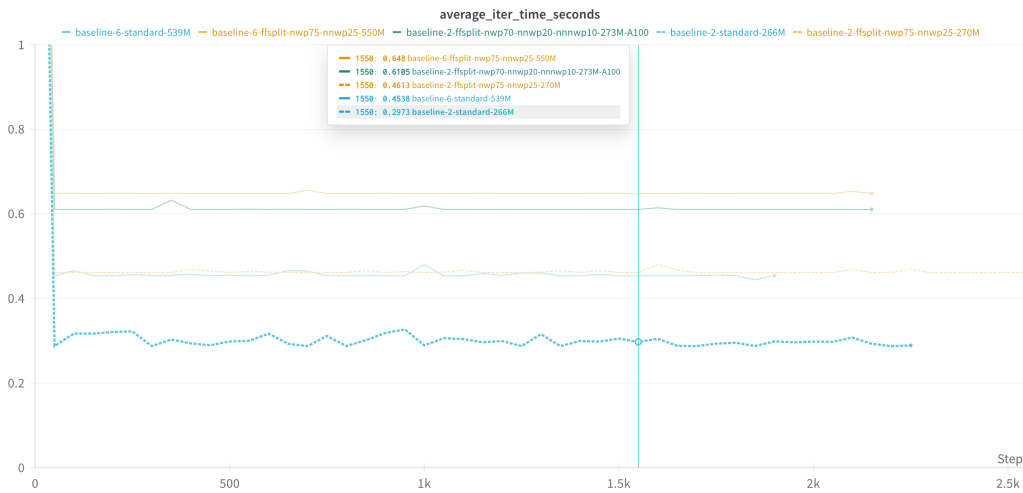

As expected, scaling up also decreases the relative gap in iteration time (a disconnected but rough proxy for flops) between a 1GRAM vs. 2GRAM model. Compared to the 1GRAM version, the 2GRAM version of a ~260M parameter model (baseline-2) is 64% slower, whereas it is only 42% slower for a ~540M parameter model (baseline-6). This gap shrinks as model size increases.

Control experiments

We can also attempt to control for the extra compute by training a 1GRAM next word prediction model with the same architecture as its multi-token counterparts.

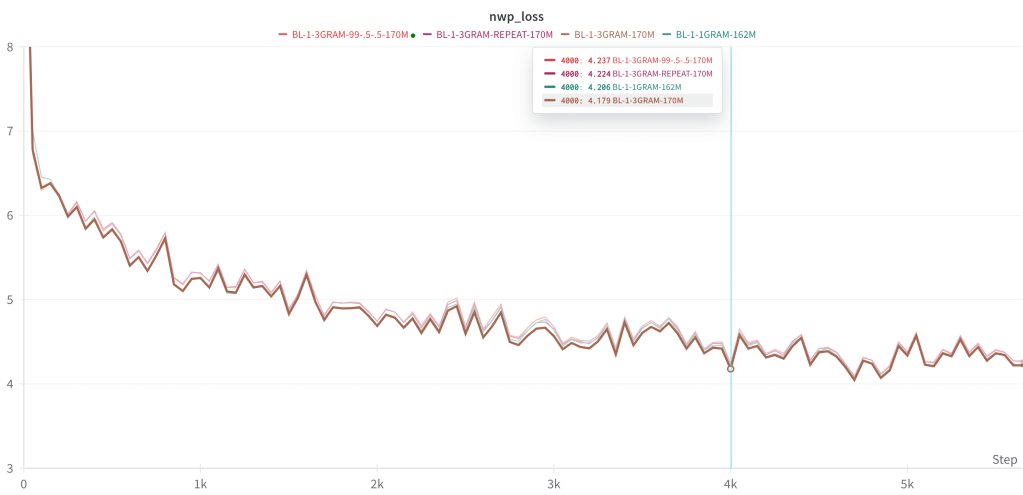

Specifically, we train a 3GRAM multi-token architecture to repeatedly predict only the next token, instead of other tokens. (Though I don’t have any reason to think this isn’t just equivalent to the 1GRAM model with redundant compute.) In addition, we train a 3GRAM model with a loss function extremely skewed towards the next token. That is:

Total loss = (.99 * loss on token 1) + (.005 * loss on token 2) + (.005 * loss on token 3)

The purpose of these experiments is to see if there is some non-obvious, lurking advantage to the FFSplit architecture or to having larger / multiple passes in the output embedding. Admittedly, I don’t have a great argument for why this would be so, but nevertheless I would like to rule out something strange / buggy like this happening.

Both of these experiments are the same or slightly worse than the standard next token prediction architecture. Here again the 3GRAM model slightly outperforms all others.

Lastly, additional experiments to rerun these models while tracking FLOPS reveals FFSplit (blue) and the reduced FFSplit (red) are roughly equivalent in terms of loss per GFLOP:

DISCUSSION

This result was quite unexpected. Going in, my hypothesis was that multi-token models would certainly be worse at predicting the next token, but maybe under some metric we could find downstream cases where ngram models are more sample efficient or produce better text over long sequences that is not necessarily captured with next word prediction loss. That is, maybe we can find some downstream benefit in a task that requires planning for future states, perhaps reasoning or arithmetic.

So the result is very surprising for reasons I have already shared. I am cautiously optimistic, especially based on the recent results from the FAIR authors.

I will provide further discussion at a later date. At this point I am most interested in testing the FFSplit model at scale while specifically isolating and measuring next word prediction loss.

SCALING

Please understand that with my personal budget I am only able to run relatively small models for a relatively short amount of time (<=1B parameters, <=1B tokens). It should go without saying that all my results apply only at the scales I have tested. This is a very big caveat since the success of a method is largely dependent on whether it works at much larger scales, and it is very often the case that what works at small scale does not work at large scale, and vice versa. Initially I hoped that these results would inspire a lab with $$$ to test at larger scales, but it looks like FAIR has already done a great deal of work in this direction! To my mind it still remains to be seen how a) the FFSplit architecture specifically scales up, and b) what the isolated next word prediction loss looks like for FFSplit and the FAIR models.

LINKS:

Clean Colab notebook for replicating experiments (recommended)

Colab notebook containing most of the original/WIP project code (very messy.) The “standard” transformer decoder model is detailed here, all variations are essentially modifications on this.

Experimental log / notes (very messy, contains some irrelevant material on other experiments/projects, e.g. discussion of residuals/skips)

wandb (most runs are in “ngram-transformers” some are in “bench”)

FUTURE WORK / THINGS YOU SHOULD TRY

There are a lot of nice followup ideas. The primary experiment is to scale. If you want to give me compute credits or want to run the model yourself at scale please do so.

Otherwise the most immediate and obvious are essentially hyperparameters with a somewhat large search space: how to divide the loss function; how many tokens to predict; optimal architectures for generating multiple tokens. I’ll list a few here

NGRAM INFERENCE

- How useful are the n+1 gram tokens? (at small scale models they are not very good). Can we simply output n tokens at a time instead of autoregressively outputting one at a time? The FAIR paper seems to answer this in the positive.

- Confidence measures for the ngram tokens for dynamic inference? E.g. something like Mixture of Depths tries out various methods to determine a model’s “confidence” in a token: auxiliary model, softmax score threshold on logits, properties over the softmax logits distribution, etc.

LOSS FUNCTION / PRETRAINING OBJECTIVES

- Optimal number of tokens to predict? I only tested 2 and 3, the FAIR authors found 4 to be optimal.

- How to divide the loss function between predicted tokens? (75-25 for 2gram and 70-20-10 for 3gram are the best results I got, but I only tested out a handful of combinations before settling on these numbers in order to start benchmarking.) As far as I can tell the FAIR authors do not weight the loss functions and call for it in future experiments. Prophetnet uses power a power attenuation function (4).

- Enforcing syntax in the loss function or model: note that currently there is no explicit instruction of which order the words are in, the model is taught word order according to the loss associated with each output.

- It would be interesting to test how well the model knows word order under the multi-token task (against standard models, with and without RoPE).

- Affording partial credit where the model predicts the correct tokens but in the wrong order.

- Auxiliary tasks involving averaged embedding values rather than discrete tokens

- Removing word order / syntactic constraints: auxiliary tasks that ask for high information density token predictions within a window of future tokens, e.g. predicting that “baseball” will occur somewhere in the distant window of future tokens when given the input text “Babe Ruth __” : we know it is likely coming up but also know it will not be the immediate next token. (We also want some mechanism to select for high information density tokens, rather than vacuously predicting that “the” or “a” will occur within the future window.)

DOWNSTREAM PERFORMANCE

- Requires access to a large pretrained model

- What tasks would best demonstrate any benefits of a model that is “thinking ahead?” Reasoning, arithmetic, etc. I am not very familiar enough with downstream benchmarks or tasks to have a good intuition about which direction to go in at this time.

ARCHITECTURE

- How do we modify the architecture to predict multiple tokens?

- I tested many variations and settled on ffsplit as the best option. Some notes in this vein of what did and didn’t work:

- Appendix B of the paper details their alternative architectures

- Multiple output embedding matrices performed fine, but did not justify the massive parameter increase

- Simply splitting inside of the feedforward layer of the last transformer layer did not work well. Adding another feedforward layer (including nonlinearity) on top (this is “ffsplit” effectively) seems necessary. The authors tested a linear layer without nonlinearity but do not appear to have tested “ffsplit” the variation that works best in my experiments.

- Where/if to add norms / nonlinearities along the way. There are a lot of variations to try.

- Providing separate self-attention transformer layers following the shared transformer layers (“heads” and “trunk” in the paper, respectively) seemed like the most obvious but did not work for me. The authors did not try multiple separate layers on top of the “trunk” either.

- I tried several other variations that performed worse than FFSplit, see code for model names and brief descriptions.

- I didn’t try causal or conditional generation over the tokens, which strikes me as too compute-intensive / fiddly to work as a general purpose pretraining task. The authors mention this but but don’t mention how it does.

SCALING

- How does this approach scale under the different configurations discussed above?

GLOSSARY FOR WANDB RUNS:

- “baseline-x” refers to a specific model size/architecture spec. These are just iterations on scaling up/down model size. The baselines are selected for benchmarking based solely on their per-parameter performance for standard language modeling. That is, they are not cherry-picked for NGRAM performance.

- “Standard” or “1GRAM” refers to a vanilla transformer decoder language model

- “2GRAM” or “3GRAM” refer to multi-token models

- “ffsplit,” “single-embedding,” “hydrasplit,” “blocksplit,” “ffdivide,” “ffreduce,” etc. refer to model architecture modification used to generate multiple token embeddings, for which there are many design options. “ffsplit” (described below in detail) is the paradigm used unless specified otherwise. All others are described in the code very messily, unfortunately. Interestingly the FAIR authors use what looks like the equivalent of “hydrasplit,” which I tried but had no success with.

- “NWP,” “NNWP,” and “NNNWP” refer to next word prediction, next-next word prediction, next-next-next word prediction. The numbers associated with these designate the distribution of loss across these predictions, e.g. “nwp70-nnwp20-nnnwp10” means a 3GRAM model where total loss is (70% NWP) + (20% NNWP) + (10% NNNWP), “nwp75-nnwp25” means a 2GRAM model where total loss is (75% NWP) + (25% NNWP).

- “-000M” is the parameter count of the model.

- As a summary, “baseline-1-single-embedding-ffsplit-nwp70-nnwp20-nnnwp10-160M” means a 3GRAM, 160M parameter model with architecture size spec #1, a single embedding layer, using ffsplit for multi-token prediction and the loss function allocated 70% to the first token, 20% to the second token, and 10% to the final token.